Indian Dress Definition

Source(Google.com.pk)In India, colour is not merely a means of ornamenting the body, artefacts or architecture. It is an integral part of all facets of life, incorporated into the everyday fabric of Indian society and richly imbued with a plethora of symbolic nuances. This phenomenon is most apparent perhaps in the traditional garments worn by the women of various communities across the Indian subcontinent, wherein the use of colour has historically served as a marker of social and cultural identity in this vast land peopled by many communities.

In the Vedic period (2000 BC- 600 BC), particular colours came to be associated with specific castes (a system of social stratification based on hereditary occupation), a phenomenon evidenced by the use of the Sanskrit word varna (colour) to denote caste. Although the caste system no longer exists in India per se, clothing traditions in India often reflect historic caste-colour associations. White came to be associated with the purity and light and was reserved for the use of the highest castes, i.e. the Brahmins. However, exceptions to this norm may be seen in the western and southern regions of India where traditional Brahmin saris were often brightly coloured. Across India, white is extensively worn by men, although usually in a somewhat tinted form or with another colour as an embellishment. Pure white is usually worn only as a sign of mourning by men and women alike and accordingly, widows in north India traditionally wear white saris devoid of any coloured embellishment or patterning. Married women generally never wear any white coloured garments. In some instances, as in the sanetar sari of Gujarat, they often wear a combination of red and white which is representative of both the aspects of masculine and feminine. In other communities, such as the Santhal tribals, white is seen as a symbol of chastity and accordingly, the bride usually wears a khandi i.e. a white sari with a purple border. Likewise, Assamese brides can be seen in the mekhala chaddar, a white sari embellished with intricate thread work and zari (metallic threads). The colour white is also seen as a negation of splendour and therefore signifies simplicity. Thus Hindu priests often wear white as do the members of the austere Jain Svetambara sect who wear sveta or white clothing.

Red was traditionally associated with the Kshatriya warrior caste but is also regarded as an auspicious colour, referred to in Vedic scriptures as ‘enchanting to the gods and goddesses’. Traditionally obtained from the manjith or madder plant, the colour red is associated with blood or the life force. It is also strongly associated as a symbol of fertility due to its associations with the Goddess Lakshmi and accordingly, saris worn by brides in many regions of North India and by Brahmin brides in some South Indian communities are usually coloured a vibrant red. For instance, the red Benarasi sari (a rich brocade characterised by its lavish use of golden zari threads) is worn by brides in Punjab while the maroon and gold-bordered koorap-podavi is worn by brides from the southern state of Tamil Nadu. Further, married women in many regions of India apply red turmeric powder on their foreheads or on their hair as a symbol of their marital status. Green, likewise associated with fertility and nature, is teamed with a red border for the traditional saris worn by Maharashtran brides.

Regarded as the colour of religion and asceticism, saffron yellow or orange was widely worn by Hindu monks and mendicants as well as by other individuals in order to symbolise their having relinquished their caste and family to lead a spiritual life aimed at releasing themselves from the endless round of rebirths. In north India, yellow is also thought to signifies prosperity due to its association with good harvests of wheat and mustard. Therefore, in Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh, the maternal grandmother of the bride usually gifts a piri or yellow sari to the bride for the lagan or wedding while the groom dons a golden yellow dhoti. In the Kangra region, the maternal aunt used to stitch a yellow full-length ling-chola or tunic during the once-lengthy pheras or nuptial ceremony. Yellow was also regarded as a highly auspicious colour and accordingly, Hindu deities are often dressed in the golden pitambaram. Shawls or head coverings of the same colour are also draped on the bride or groom in various communities –a yellow odhni or shawl is placed on the grooms shoulders during the wedding ceremony in Uttar Pradesh while elaborately embroidered phulkari shawls are given to the bride in Punjab. In the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, on the first day of the Hindu wedding ceremony, the bride is washed in turmeric to ritually purify her, during and after which she wears a yellow sari. Yellow saris are also commonly worn during the climax of Tamil and Telegu wedding ceremonies among non-Brahmin communities; a yellow navarri silk sari is likewise worn by Maharashtrian brides during the puja or ritual ceremonies. A yellow sari is also traditionally worn during the seven days following the birth of a child, when the mother conducts various pujas. Obtained from the expensive saffron leaves, saffron yellow or kesariya as it is known in North India, was historically worn by the wealthy, especially on occasions such as weddings. In Rajasthan, the colour is also associated with bravery and was worn by the warrior Rajput class when they rode into battle.

The colour blue, historically obtained by fermenting indigo, was considered ritually impure and was therefore associated with the Sudras and outcastes. Black, created by deepening the indigo mix, was likewise deemed inauspicious. Both colours, by c 1400 came to symbolise sorrow and ill-omen, and were worn by some communities during the mourning period. During the mid-nineteenth century, this association died out and blue as well as black patterning on white saris came to be widely worn by older married women, especially in the eastern regions of the country. In western India, blue was commonly worn by many tribal and low-caste groups, as it was seen as protection against the evil eye.

The colours worn by various communities may also be seen as a response to the climate they habituate. Thus, one may see the austere white and gold kasava sari worn in the lush tropical greenery of Kerala and the brilliantly coloured and embroidered garments of the Rabari nomadic tribes in the desert lands of Kucchh. The colour-climate nexus is also translated into the selection of garments of specific colours in accordance with the changing of the seasons. For instance, in the state of Rajasthan, orange and golden are favoured for garments worn on the occasion of the New Year or the lunar month of Chaith. In high summer, cooler colours such as kapasi or light yellow, javai or light peach, and motia or pearl pink are worn. Savan or the rainy season is greeted with green tie-dyed leheriya dupattas or stoles, which depict prosperity and joy. A red odhna or head covering is worn during the Teej festival, when women pray for the long life of their husbands. The festival of lights or Diwali is also brightened with colours of red and yellow. Women of the Rajput warrior community usually wear a deep purple odhni on Diwali.

The nature of the colours used in the garment may also be defined by its intended end-use. For instance, in Rajasthan, kachcha or temporary colours are traditionally used for the garments of unmarried and married women while widows only use the pakka or permanent colours. Kachcha colours such as red, yellow, parrot green and saffron thus represent themarital phase, with widowhood denoted by grey, brown, dark green, dark blue and maroon.

Colour has long served as a marker of identity in the Indian subcontinent. The hues of a garment denote not just personal sartorial preference but convey all sorts of social data, ranging from the wearer’s age and marital status to his/her community of origin. Although coloured garments may have had, at some point in India’s history, prescribed caste-based associations, India’s textile history is not one of rigid norms. Since the very initiation of dye technology in India, master weavers, dyers, embroiderers and printers have experimented with new dyestuffs and techniques to create an incredibly varied palette that has contributed to the country’s vibrant and dynamic textile traditions.

For more from India's Craft Revival trust, visit www.craftrevivaltrust.org.

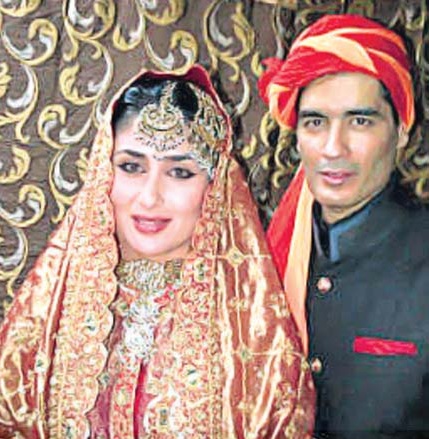

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

Indian Dress Immage Photo Pictures

No comments:

Post a Comment